From the Basic Perinatal Matrices (BPM) to the Grof Promulgation Matrices (GPM)

A cartography of how the pseudoscience of Stan and Christina Grof is disseminated and normalised.

Welcome to my Substack, Deep Breaths. I am a PhD candidate looking at the use of touch in psychedelic therapies. Deep Breaths is a personal project dedicated to critically examining the Grofs + Holotropic Breathwork and their influence on contemporary psychedelic therapies. All opinions expressed here are entirely my own.

Note: This post contains references to sexual violence, the recovery of repressed memories, and cult-like dynamics in therapeutic settings.

If you are concerned about a therapist or cult-like dynamics, you can find more resources on therapy harm here and on spirituality and healing cults here.

“So then Stan Grof, who was the leading LSD research and my mentor, and I met him in 1972 and 1982, and he’d written a book called Realms of the Human Unconscious, Observations from LSD Research, and he talked about it as the cartography of the unconscious, sort of the maps to the unconscious. And then Ralph Metzner, who was with Ram Dass and Leary at Harvard, Ralph Metzner had wrote a book called Maps of Consciousness. So I said, okay mpas cartography, we got maps, we got a P in there for psychedelic. Now I just have to figure out what the M, the A, and the S would stand for…”

- Rick Doblin, founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) on “Greater Good Radio”, March 2025

MAPS loves a map.

While thinking about the Grofs and how their ideas are disseminated and normalised today, I decided to make a map. The map started as concentric circles and tables of people and ideas.

Who are the thinkers that inspired Stan and Christina Grof? Who are the contemporaries and thought-leading supporters? Who are the certified Holotropic Breathwork facilitators? Who is bringing Holotropic Breathwork into clinical practice? Who repeats Grofian theory uncritically, and who subtly legitimises them without necessarily even being aware of who Stan or Christina Grof is? How are ideas like psychedelics allowing access to the collective unconscious, past-life regression, alien encounters, astrological determinism, and the need to re-experience birth trauma, becoming normalised through the acceptance of the Grofs in mainstream psychedelic therapy?

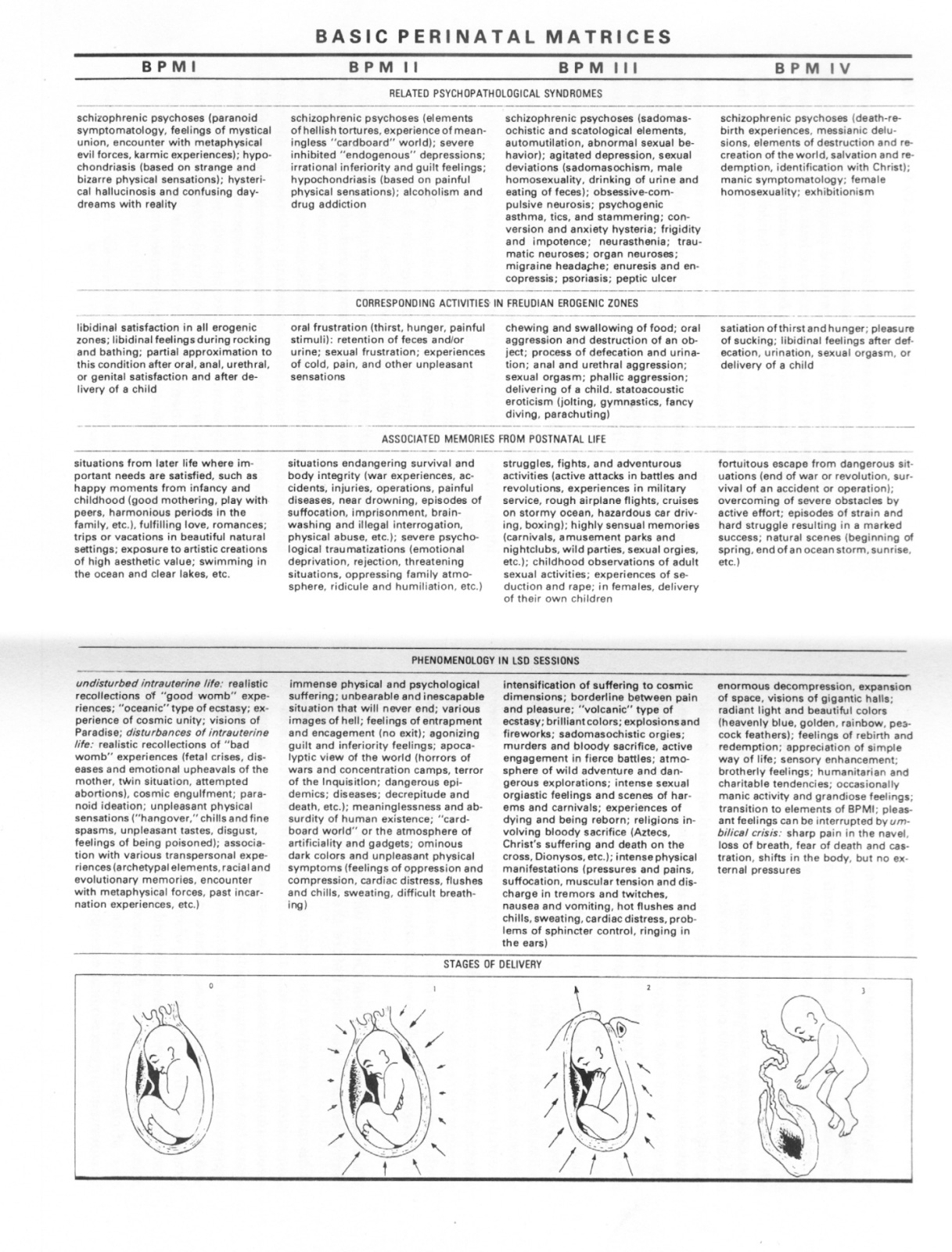

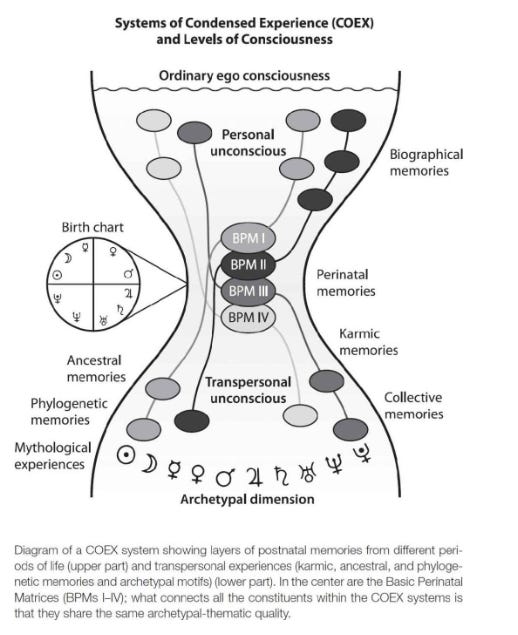

I realised that there were four broad categories of people involved in spreading Grofian theories, intentionally or otherwise. From there, loosely inspired by Stan’s four Basic Perinatal Matrices (BPMs), I drafted the Grof Promulgation Matrices (GPMs).

Before I go on about the GPM, I’ll give some brief context on the BPM.

Stan’s theoretical project of mapping the psyche begins with the claim that Freud’s model of consciousness didn’t go far enough. Through his LSD research in Czechoslovakia, Stan claims he ‘discovered’ that the psyche and life experiences are shaped by archetypal and transpersonal forces. Most importantly, he also ‘discovered’ that our physical birth into the world was an original trauma that needed to be resolved. Stan’s BPM are thus a map of the psyche based on his observations of patients.

It’s important to note that although Stan tries to position his observations as a kind of neutral scientific observation, his entire reason for entering medical school was to becoming a Freudian psychoanalyst.

In, The Story Search for the Self (1990), co-authored with Christina, Stan writes:

“I was born in 1931 in Prague and spent my childhood partly in that city and partly in a small Czech town. In the early years of my life my interests and hobbies already reflected a great curiosity about the human psyche and culture. My actual involvement with psychiatry and psychology started when I was finishing high school. A close friend of mine lent me, with warm recommendations, Sigmund Freud's Introductory Lectures to Psychoanalysis.

Reading this book turned out to be one of the most profound and influential experiences of my life. I was deeply impressed by Freud's penetrating mind, his unrelenting logic, and his ability to bring rational understanding to such obscure areas as the symbolism and language of dreams, the dynamics of neurotic symptoms, the psychopathology of everyday life, and the psychology of art. Since I was close to graduation, I was about to make some serious decisions about my future. Within a few days of finishing Freud's book, I decided to apply to medical school, which was a necessary prerequisite for becoming a psychoanalyst.”

Grof then jumps to explain how he was a staunch atheist, reinforced with six years of Marxist materialist ideology. He describes being convinced of the mainstream psychiatric research, suggesting visions and mystical experiences were psychopathologies.

““I studied a broad spectrum of scientific disciplines under these special circumstances, which only reinforced my conviction that any form of religious belief or spirituality was absurd and incompatible with scientific thinking…Though I had little reason to doubt the beliefs of so many prominent scientific and academic authorities in this regard, I often wondered why millions of people throughout history allowed themselves to be so deeply influenced by visionary experiences if those experiences were nothing but meaningless products of brain pathology. However, this doubt was not strong enough to undermine my trust in traditional psychiatry”.

After professing his allegiance to materialsit science, Stan then inexplicably jumps to describing how he joined a small psychoanalytic group in Prauge. This nonchalant jump from one contradictory idea to the next is characteristic of the logical flow his work tends to take. What’s most impressive though, is how Stan always gives the impression of making sense. Everything sounds so believable.

But to recap, Stan has just told us that: he always had an interest in psychoanalysis; he went to medical school for the sole reasons of become a Freudian analyst; in medical school, he was a total materialist and believed anything spiritual was absurd and incompatible with science; and also in medical school, he joined an obscure outlawed Freudian psychoanalysis training program. With this logic, Stan manages to somehow weave his psychoanalytic training into his medical training and use this as a legitimate starting point for development of a methodologically rigorous theory.

Another step to framing his theories as science involves how he situates himself in the history of psychology. In Holotropic Breathwork (2010), the Grofs give an overview of the development of American psychology that omits the entire cognitive revolution:

“In the middle of the twentieth century, American psychology was dominated by two major schools—behaviouism and Freudian psychoanalysis. Increasing dissatisfaction with these two orientations as adequate approaches to the understanding of the human psyche led to the development of humanistic psychology”.

This is partially true, but it leaves out what is widely considered to be the major development in American psychology in the 1950s/60s: cognitive psychology. Cognitive psychology brought attention to the empirical study of internal mental processes like memory, perception, language, and problem-solving. This included the development of quantitative measures for cognitive processes and research methodologies like the first randomised-controlled trial.

Even the Journal of Humanistic Psychology acknowledges that humanism was secondary to ‘the cognitive revolution’.

Rarely do we speak of the humanistic revolution in psychology. It happens now and again, but not nearly enough….Could it be because the humanistic revolution is not believed to have resulted in widespread changes in the mainstream of psychological thought? If this is the reason that some psychologists are reticent to use the phrase “humanistic revolution,” I submit that it is not a good enough reaspn..Historically speaking, it was most certainly the combined influence of humanistic psychology and cognitive psychology that ended behaviorism’s stranglehold on psychology, yet “the humanistic revolution” is a rarely used expression, while “the cognitive revolution” is common parlance…Ironically, cognitive psychology is more often dubbed revolutionary among psychologists because of the mainstream success it has garnered by not deviating too quickly and/or too radically from the rationalism, naturalism, and methodological myopia of the status quo. Against this historico-theoretical background, the current article is a tribute to the revolutionary proposal first offered by humanistic psychology in the mid-20th century. To those who dared to be different: astra inclinant, sed non obligant!1

Leaving out the cognitive revolution from the history of mid-century psychology is like talking about human violence and leaving out the entire history and development of feminist scholarship, something Stan also does.

As I see it, Stan is a creative who writes stories and curates aesthetically driven experiences in Holotropic Breathwork workshops. By creating a world where the cognitive revolution (and feminism) are distant concerns of no relevance to his work, he’s better described as an auteur than a psychiatrist.

By the time Stan was developing his theories, Freudian psychoanalysis had already been extensively critiqued and, for good reason, fallen out of favour. Stan, however, began his work in communist Czechoslovakia, where Freud’s writings were banned and had to be read covertly. It seems he built much of his critique on the premise that Freud’s model still dominated Western psychiatry when, in fact, it no longer did.

Stan had to have known this—he emigrated to the United States in 1967. And yet, by 1975, he still writes as though he's the main character of Good Bye Lenin!, nostalgically clinging to the forbidden texts of psychoanalysis as if they were the cutting edge of psychiatry.

At Esalen, Stan is able to stay in this comfortable but myopic world of privilege and fantasies about transforming humanity.

Stan creates a bubble of simplistic explanations for his work, where the real problem is that Freud didn’t go far enough. In one deep breath, it’s as if Grof legitimates his rejection of Freud, and simultaneously, every major psychological and psychiatric development since Freud. His theories disregard important shifts like the depathologisation of homosexuality, the feminist critiques of psychiatry, the emergence of trauma-informed care, and the questioning of cathartic “abreaction” techniques.

This retro-fictional world is the backdrop for the Basic Perinatal Matrices.

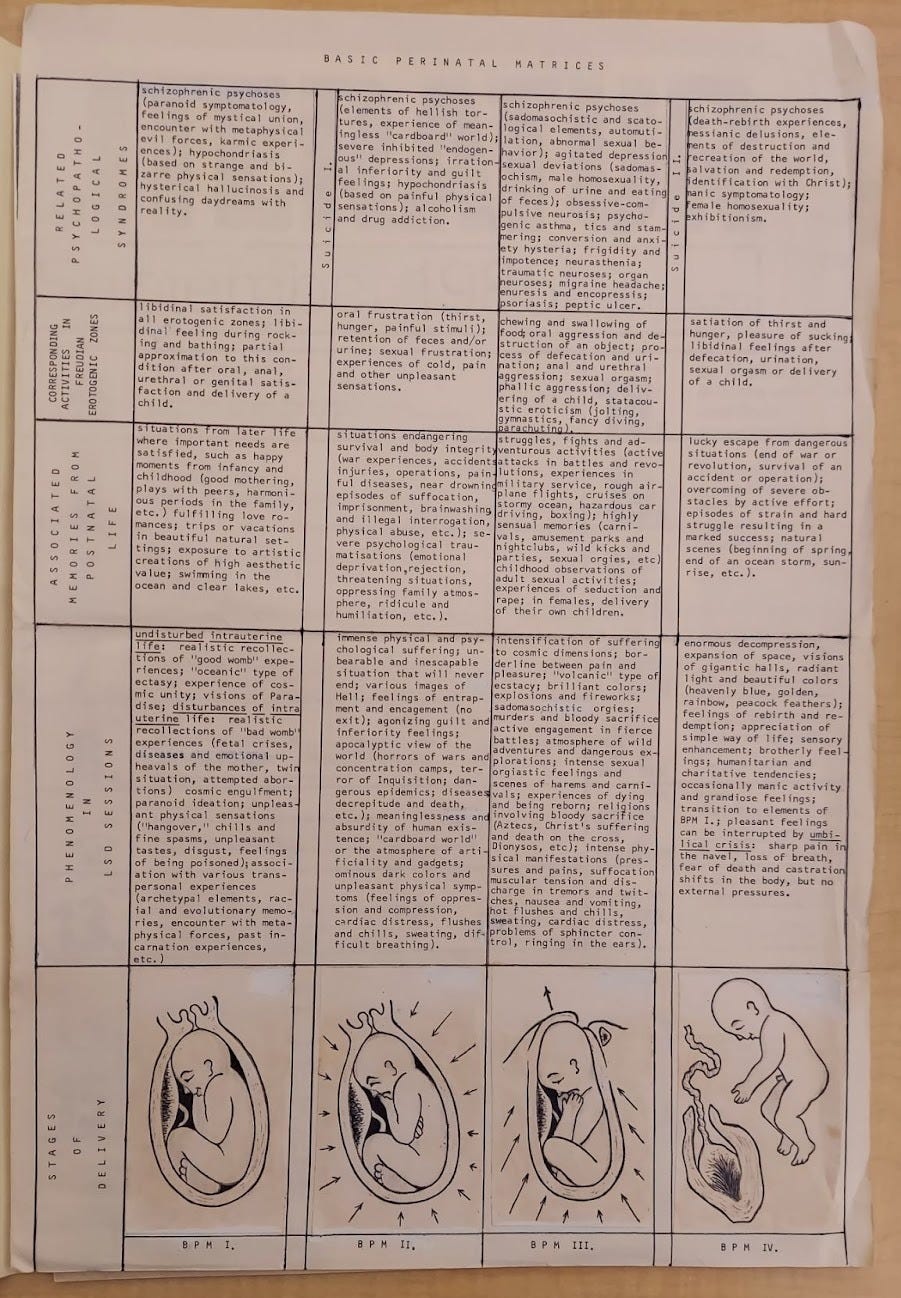

The Basic Perinatal Matrices (BPMs) map four stages of the birth process onto recurring psychological patterns/pathologies, which he believes can be accessed and healed through special non-ordinary states like those induced by Holotropic Breathwork or psychedelics (but not alcohol or other drugs, because they’re not special ones).

From The Way of the Psychonaut Volume One (2019):

The conscious reliving and integration of the trauma of birth plays an important role in the process of experiential psychotherapy and self-exploration. The experiences originating on the perinatal level of the unconscious appear in four distinct experiential patterns, each of which is characterized by specific emotions, physical feelings, and symbolic imagery. These patterns are closely related to the experiences that the fetus has before the onset of birth and during the three consecutive stages of biological delivery. These experiences leave deep unconscious imprints in the psyche that later in life have an important influence on the individual. I refer to these four dynamic constellations in the deep unconscious as Basic Perinatal Matrices or BPMs…“The BPMs represent important gateways to the collective unconscious described by C. G. Jung. Identification with the infant facing the ordeal of the passage through the birth canal seems to provide access to experiences involving people from other times and cultures, various animals, and even mythological figures. It is as if by connecting with the fetus struggling to be born, one connects in an intimate, almost mystical way with other sentient beings who are in a similar predicament….

The encounter with perinatal matrices can occur in sessions with psychedelic substances, during Holotropic Breathwork, in the course of spontaneous psychospiritual crises (“spiritual emergencies”), or in actual life situations, such as during childbirth or in near-death experiences (NDEs) (Ring 1982). The specific symbolism of these experiences comes from the collective unconscious, not from the individual memory banks. It can thus draw on any historical period, geographical area, and spiritual tradition of the world, quite independently from the subject’s cultural or religious background.

Individual perinatal matrices have connections with certain categories of postnatal experiences that share the same archetypal qualities and belong to the same COEX systems. They also have associations with the archetypes of Mother Nature, the Great Mother Goddess, Heaven, and Paradise (BPM I); the Terrible Mother Goddess and Hell (BPM II); Sabbath of the Witches and satanic rituals (BPM III); Purgatory and deities from different cultures representing death and rebirth (BPM III-IV), and divine epiphany, the alchemical cauda pavonis (peacock tail), and rainbow arc (BPM IV). Later in the book, we will explore the remarkable parallels between the phenomenology of BPMs I-IV and the astrological archetypes Neptune, Saturn, Pluto, and Uranus…

Reinforced by strong, emotionally charged experiences from infancy, childhood, and later life, perinatal matrices can shape our perception of the world, profoundly influence our everyday behavior, and contribute to the development of various emotional and psychosomatic disorders. On a collective scale, perinatal matrices play an important role in religion, art, mythology, philosophy, and various sociopolitical phenomena, such as totalitarian systems, wars, revolutions, and genocide. We will explore these broader implications of perinatal dynamics in later chapters.”

Grofian theory, particularly the Basic Perinatal Matrices (BPM), invites individuals to reinterpret psychological distress as evidence of a profound “spiritual emergence,” encouraging re-experiencing of birth and death-like states.

This, to me, is the most notable difference between Grofian theories about spiritual emergencies and Mad Liberation theories around depathologising psychosis. Holotropic Breathwork and the associated theories induce untethered states, under the guise of being therapeutic and ‘evidence-based’.

My Grof Promulgation Matrices (GPMs) are about mapping how Grofian theories are ‘delivered’ into the world. The GPMs map the different kinds of people and positions involved in legitimising Grof’s work. Here’s a brief overview that I’ll build on in later posts:

GPM I: Primal Union with the Mother, Esalen.

The cosmic ideological bliss among the allied thought leaders of the New Age/ Transpersonal/Human Potential Movement. Esalen served as a womb, the immersive environment of proto-spiritual psychology. The best resource I found to help 'map’ GPM I is the acknowledgements section of The Way of the Psychonaut and the book Psyche Unbound: Essays in Honour of Stanislav Grof (2022, published by MAPS). I’ll start getting into this in the next post (probably), with a focus on Richard Tarnas first.

GPM II: Cosmic Engulfment with Holotropic Breathwork workshops.

Now really developing as its own in the womb, GMP II covers certified Holotropic Breathwork facilitators. Just as BPM II involves mythic engulfment in the womb, the experience of being devoured, GPM II is characterised by full absorption into the Grofian theories. No exit or Hell, just total missionary zeal, upholding Grof's legacy.

GPM III: The Death-Rebirth Discourse (Strategic Legitimisers, Plausible Deniability).

Just like BPM III, GPM III is probably the worst. These are the academics, researchers, and public figures who praise Grof's influence or borrow from his frameworks, but maintain a plausible deniability about the extremeness of his theories. They’ll be the first to say, “I didn’t know Grof said that”, despite declaring that Grof’s book was transformational for them. They often work closely with people in GPM I and II, without questioning their devotion to Grofian theories. This is why people in GPM I and II are so fond of them as colleagues—people in GPM III leave their door open for Grof (and subsequently, I would argue, pretty much anything else). They might say things like, “The Inner Healing Intelligence is a useful metaphor”, or “Grof is about 50-60% right”.

GPM IV - Unconscious Grofians.

GPM IV is Grof unleashed into the world, detached from the cosmic womb and now autonomous. The key feature of GPM IV is repeating Grofian/Holotropic Breathwork ideas, without knowing Stan or Christina Grof. A prime example would be this medium article about inner healing intelligence written by Hillary Lin, MD, with no mention of or public connections to Grof.

Lin writes,

“In psychedelic health work, you often hear about the inner healing intelligence. Psychedelics help us bring down our defenses and learned habits so that this healing intelligence can do its work.

I was extremely confused about this for some time. The phrase, “inner healing intelligence” makes it seem like there is a little therapist living within us resolving all the emotional hurts we experience day to day. I am admittedly a materialist and initially dismissed this thought as kinda fantastical.

But then I found an analogy that made the phrase make sense.

When you break your arm, you need to set the broken bones properly, put it in a cast and sling, and give it a break for a few weeks….

The same thing happens with emotional healing. When we suffer an emotional trauma, whether it is a mild slight or a severe, life-altering event, our body’s natural instinct is to protect, and then heal. The issue, for most of us, is that we live in an environment which is not set up for optimal healing. There are not enough emotional doctors out there to place casts for the millions of emotional traumas we experience...

So inner healing intelligence really is a thing, and not so fantastical as I originally thought. We just need to nurture it to help us grow to become the fulfilled and self-actualized humans we all have the potential to be.”

This is a dangerous oversimplification of the idea of the inner healing intelligence. Instead, as Doblin indicates in his talk on Stan Grof’s contributions to psychedelic research, a key idea that Lin misses is the “let go” part. The “Lesssoins from Stan for our protocols” is to “amplify” the “death-rebirth process”.

And what is the reason why you would amplify the death-rebirth process? Because your inner healing intelligence only gives you what you need to heal. What do you need to heal? To re-experience traumas, including your own birth, so they can be ‘properly’ integrated.

What unites all four matrices is a willingness to treat Grofian theory as if it belongs at the table of serious discourse about clinical applications for psychedelics—it doesn’t.

Google: "The stars incline us, but do not bind us." It emphasises the concept of free will, suggesting that while influences (like the stars or our environment) may sway us, they don't dictate our actions or destiny. We have the ability to choose our own path despite any inclinations or predispositions.