An introduction to Holotropic Breathwork through the words of Christina and Stan Grof

A selection of key quotes and images from the books and documentaries on Holotropic Breathwork.

Note: This post contains references to sexual violence, the recovery of repressed memories, and cult-like dynamics in therapeutic settings. It also includes images of participants being physically restrained during Holotropic Breathwork sessions, as well as discussion of abuses in the MAPS Phase II MDMA trial.

If you are concerned about a therapist or cult-like dynamics, you can find more resources on therapy harm here, and on spiritual/healing cults here.

I think a lot of people assume Holotropic Breathwork is a fairly innocuous practice that is more or less like the ‘breathwork’ at the start of a hot yoga class. “Breathwork” is a broad term covering many lineages. Lots of people know about breathwork from the icebath guy or as an atheoretical coping mechanism taught in corporate mental health trainings.

A 2023 review of high-ventilation breathwork practices by Fincham et al. gives an overview of breathwork:

“Breathwork is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “any of various exercises, techniques, and therapies that involve manipulating the manner in which one breathes” (OED, 2023). This broad definition of breathwork encompasses myriad different practices, reflecting its multifaceted historical origins and inspirations, and is currently receiving increased interest as an alternative (or adjunct) therapeutic to pharmaceuticals for the alleviation of psychological distress and physical discomfort….The growth in scientific interest into breathwork parallels its explosion in public visibility in the media and popularity across the general population: while it is hard to estimate precisely how many people regularly practice breathwork techniques, there are likely to be tens of millions of breathwork practitioners worldwide, since just one breathwork program—Sudarshan Kriya Yoga—is recorded to have been taught to over six million people in 152 countries (Zope and Zope, 2013).”

Fincham et al. provide the following diagram of practice. Holotropic breathwork is listed under Reichian psychotherapy, alongside rebirthing therapy.

There’s a lot to be said about these dotted lines, but this post is about looking at how Christina and Stan describe Holotropic Breathwork, so I won’t go further on that for now.

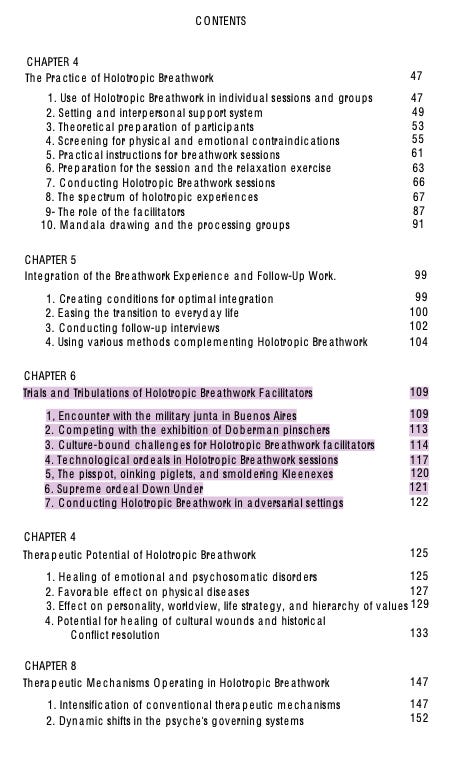

Holotropic Breathwork, 2010

Stan and Christina Grof’s Holotropic Breathwork: A New Approach to Self-Exploration and Therapy (2010) is the most comprehensive resource on the method they developed. The book gives a clear overview of the entire philosophical and experiential framework behind Holotropic Breathwork. Here’s some of the chapter content:

Below is an overview of Holotropic Breathwork from the book, and other quotes that stood out to me on the practice. Bold highlight added by me:

Holotropic Breathwork is a powerful method of self-exploration and therapy that uses a combination of seemingly simple means—accelerated breathing, evocative music, and a type of bodywork that helps to release residual bioenergetic and emotional blocks. The sessions are usually conducted in groups; participants work in pairs and alternate in the roles of breathers and ‘'sitters.” The process is supervised by trained facilitators, who assist participants whenever special intervention is necessary. Following the breathing sessions, participants express their experiences by painting mandalas and share accounts of their inner journeys in small groups. Follow-up interviews and various complementary methods are used, if necessary, to facilitate the completion and integration of the breathwork experience.

In its theory and practice, Holotropic Breathwork combines and integrates various elements from depth psychology, modern consciousness research, transpersonal psychology, Eastern spiritual philosophies, and native healing practices. It differs significantly from traditional forms of psychotherapy, which use primarily verbal means, such as psychoanalysis and various other schools of depth psychology derived from it. It shares certain common characteristics with the experiential therapies of humanistic psychology, such as Gestalt practice and the neo-Reichian approaches, emphasizing direct emotional expression and work with the body. However, the unique feature of Holotropic Breathwork is that it utilizes the intrinsic healing potential of non-ordinary states of consciousness….

Further in the Chapter “Essential Components of Holotropic Breathwork”:

This method of therapy and self-exploration combines very simple means to induce holotropic states of consciousness—faster breathing, evocative music, and releasing bodywork—and uses the healing and transformative power of these states, Holotropic Breathwork provides access to biographical, perinatal, and transpersonal domains of the unconscious and thus to deep psychospiritual roots of emotional and psychosomatic disorders. It also makes it possible to utilize the powerful mechanisms of healing and personality transformation that operate on these levels of the psyche. The process of self-exploration and therapy in Holotropic Breathwork is spontaneous and autonomous; it is governed by the inner healing intelligence of the breather, rather than guided by a therapist following the principles of a particular school of psychotherapy.

However, most of the recent revolutionary discoveries concerning consciousness and the human psyche are new only for modern psychiatry and psychology. They have a long history as integral parts of ritual and spiritual life of many ancient and native cultures and their healing practices. They thus represent rediscovery, validation, and modem reformulation of ancient wisdom and procedures, some of which can be traced to the dawn of human history. As we will see, the same is true for the principal constituents used in the practice of Holotropic Breathwork—breathing, instrumental music, chanting, bodywork, and mandala drawing or other forms of artistic expression. They have been used since time immemorial in sacred practices of ancient and native cultures….

The Grofs often refer to Holotropic Breathwork as grounded in traditional or “Indigenous wisdom”. It’s a bit of an audacious claim for the hodgepodge of decontextualised practices they combine with an apparently ‘scientific’ grounding to their theories on reliving birth and past-life traumas.

The Grofs go on to detail various breathing practices and language for breath across history.

“Since earliest history, virtually every major psychospiritual system seeking to comprehend human nature has viewed breath as a crucial link between the material world, the human body, the psyche, and the spirit. This is clearly reflected in the words many languages use for breath. In the ancient Indian literature, the term prana meant not only physical breath and air, but also the sacred essence of life. Similarly, in traditional Chinese medicine, the word chi refers to the cosmic essence and the energy of life, as well as the natural air we breathe into our lungs. In japan, the corresponding word is ki. Ki plays an extremely important role in Japanese spiritual practices and martial arts. In ancient Greece, the word pneuma meant both air or breath and spirit or the essence of life. The Greeks also saw breath as being closely related to the psyche….”

The list goes on. It’s an impressive and interesting summary. They continue by detailing changes and examples of the rebirth from breath:

“the original form of baptism practiced by the Essenes [an ancient mystic Jewish sect] involved forced submersion of the initiate under water for an extended period of time. This resulted in a powerful experience of death and rebirth. In some other groups, the neophytes were half-choked by smoke, by strangulation, or by compression of the carotid arteries…”

The Grofs then talk about how shifts in consciousness can be induced by manipulating the breath, through hyperventilation, breath retention, or mindful observation, as seen in practices across Hindu, Buddhist, Sufi, Taoist, and Indigenous traditions. Among the most influential is the Buddhist practice of anapanasati (mindfulness of breathing), which the Buddha used to attain enlightenment and taught as a path to liberation from suffering.

The Grofs then describe developing their practice from

“the guidance of Indian and Tibetean teachers and techniques developed by Western therapists…We came to the conclusion that it is sufficient to breathe faster and more effectively than usual and with full concentration on the inner process. Instead of emphasizing a specific technique of breathing, we follow even in this area the general strategy of holotropic work—to trust the intrinsic wisdom of the body and follow the inner clues…We have been able to confirm repeatedly Wilhelm Reich’s observation that psychological resistances and defenses are associated with restricted breathing (Reich 1949, 1961). Respiration is an autonomous function, but it can also be influenced by volition. Deliberate increase of the pace of breathing typically loosens psychological defenses and leads to a release and emergence of unconscious (and superconscious) material. Unless one has witnessed this process or experienced it personally, it is difficult to believe on theoretical grounds alone the power and efficacy of this approach.

They next discuss the healing potential of music, then bodywork in Holotropic Breathwork:

“Physical manifestations that develop during the breathing in various areas of the body are not simple physiological reactions to hyperventilation. They have a complex psychosomatic structure and usually have specific psychological meaning for the individuals involved- sometimes, they represent an intensified version of tensions and pains, which the person knows from everyday life, either as a chronic problem or as symptoms that appear at times of emotional or physical stress, fatigue, lack of sleep, weakening by an illness, or the use of alcohol or marijuana. Other times, they can be recognized as reactivation of old latent symptoms that the individual suffered from in infancy, childhood, puberty, or some other time of his or her life…

“The tensions that we carry in our body can be released in two different ways. The first of them involves catharsis and abreaction—discharge of pent-up physical energies through tremors, twitches, various movements, coughing, gagging, and vomiting. Both catharsis and abreaction also typically include release of blocked emotions through crying, screaming, or other types of vocal expression….Abreaction is a mechanism that is well known in traditional psychiatry since the time when Sigmund Freud and Joseph Breuer published their studies in hysteria (Freud and Breuer 1936). Various abreactive techniques have been successfully used in the treatment of traumatic emotional neuroses, and abreaction also represents an integral part of the new experiential psychotherapies, such as neo-Reichian work, Gestalt practice, and primal therapy….

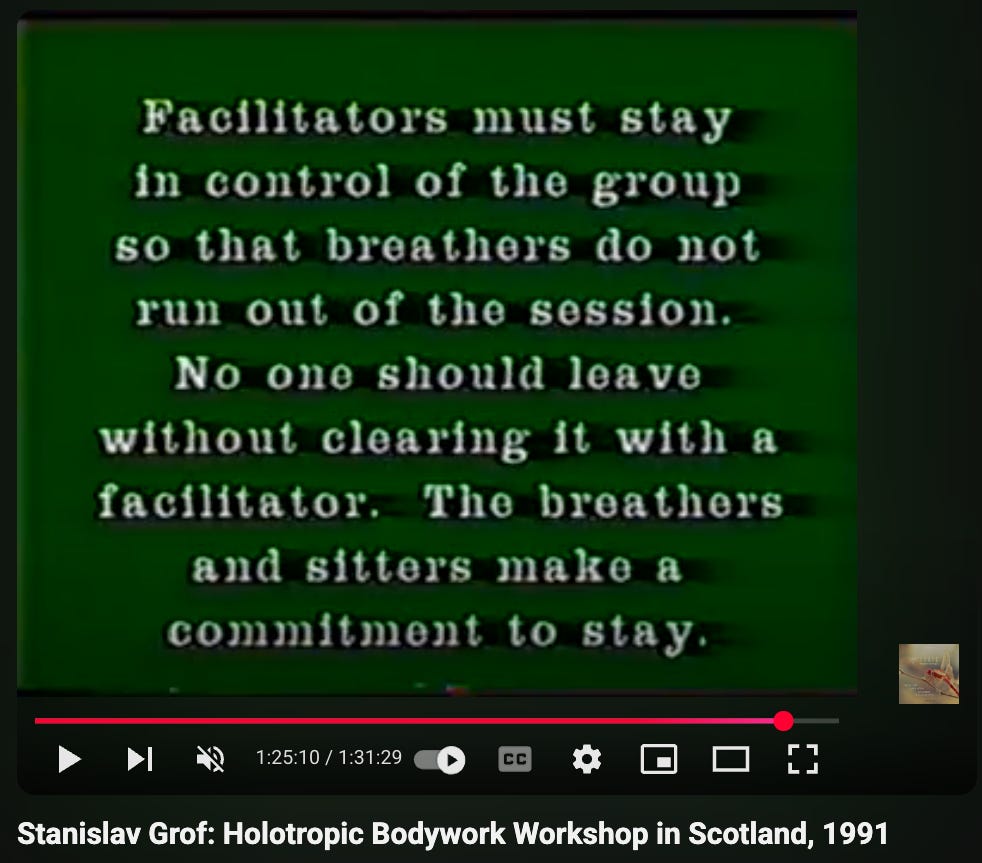

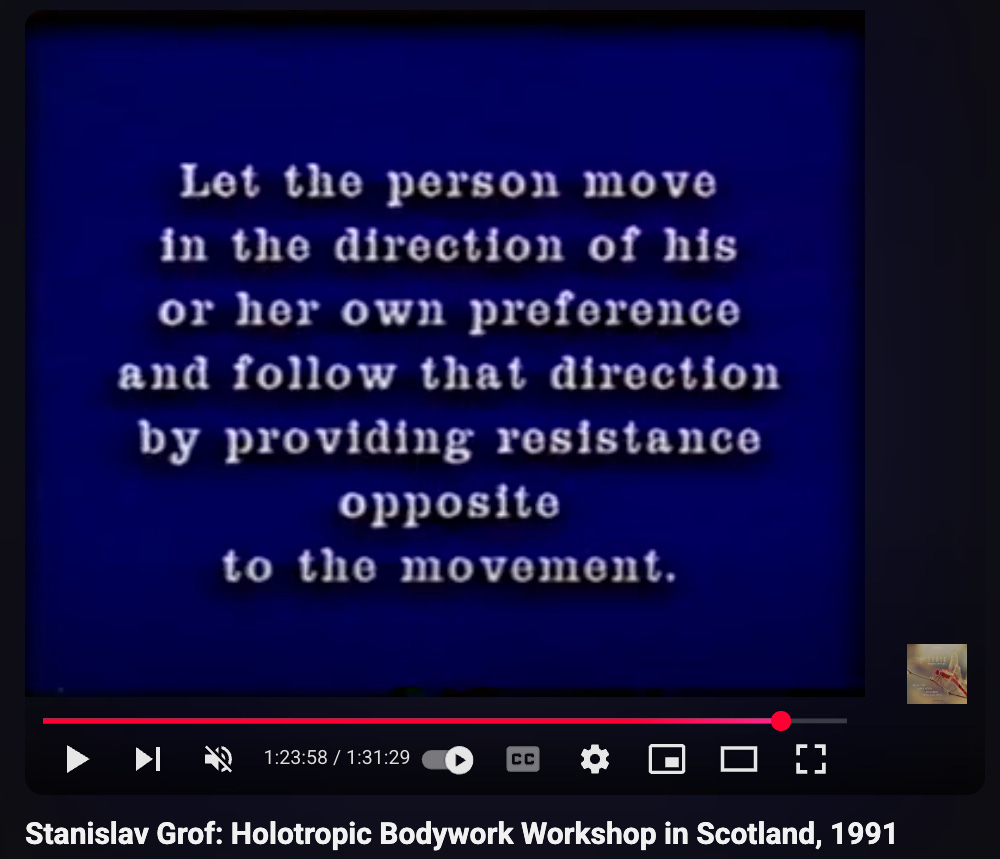

The second mechanism that can release physical and emotional tensions plays an important role in Holotropic Breathwork and other forms of therapy using breathing techniques. It represents a new development in psychiatry and psychotherapy and equals or even surpasses the efficacy of abreaction. Here the deep tensions surface in the form of unrelenting muscular contractions of various duration (tetany). By sustaining these muscular tensions for extended periods of time, the breathers consume large amounts of previously pent-up energy and simplify the functioning of their bodies by disposing of them…the general strategy of this work is to ask the breather to focus his or her attention on the area where there is a problem and do whatever is necessary to intensify the existing sensations.

The facilitator then helps to intensify these feelings even further by appropriate physical intervention from the outside. While the attention of the breathers is focused on the energetically charged problem areas, we encourage them to find spontaneous motor or vocal reactions to this situation. This response should not reflect a conscious choice of the breather, but be fully determined by the unconscious process. It often takes an entirely unexpected and surprising form-talking in tongues or in an unknown foreign language, baby talk, gibberish, voice of a specific animal, a shamanic chant or another form of vocal performance from a particular culture unknown to the breather.

Equally frequent are completely unexpected physical reactions, such as strong tremors, jolts, coughing, gagging, and vomiting, as well as various characteristic animal movements—climbing, flying, digging, crawling, slithering, and others. It is essential that the facilitators encourage and support what is spontaneously emerging, rather than apply some technique offered by a particular school of therapy. This work continues until the facilitator and the breather reach an agreement that the session has been adequately closed…by talk, that brought him back to reality.

They go on to discuss the use of “nourishing physical contact” to heal early emotional trauma. They emphasise strict ethical rules about no sexual contact, noting also that a risk with physical contact is the regressed state of the person breathing.

It is usually quite easy to recognize when the breather is regressed to early infancy. In a really deep age regression, all the wrinkles in the face tend to disappear and the individual can actually look and behave like an infant. This can involve various infantile postures and gestures, as well as copious salivation and thumb-sucking. Other times, the appropriateness of offering physical contact is obvious from the context, for example, when the breather just finished reliving biological birth and looks lost and forlorn.

Christina and Stan are big advocates of using touch to hear “trauma by omission”. They describe the “revolutionary method” developed by London-based psychoanalysts Pauline McCrick and Joyce Martin.

“During their sessions, their clients spent several hours in deep age regression, lying on a couch covered with a blanket, while Joyce or Pauline lay by their side, holding them in close embrace, as a good mother would do to comfort her child. Their revolutionary method effectively divided and polarized the community of LSD therapists. Some of the practitioners realized that this was a very powerful and logical way to heal “traumas by omission,” emotional problems caused by emotional deprivation and bad mothering. Others were horrified by this radical “anaclitic therapy“; they warned that close physical contact between therapists and clients in a non-ordinary state of consciousness would cause irreversible damage to the transference/countertransference relationship”

Stan desribes personally experiencing a profound age regression with Pauline McCrick in 1964:

“‘My own session with Pauline was truly extraordinary. Although both of us were fully dressed and separated by a blanket, I experienced a profound age regression into my early infancy and identified with an infant nursing on the breast of a good mother and feeling the contact with her naked body, Then the experience deepened, and I became a fetus in a good womb blissfully floating in the amniotic fluid.

For more than three hours of clock time, a period that subjectively felt like eternity, I kept experiencing both of those situations—“good breast” and “good womb”—simultaneously or in an alternating fashion. I felt connected with my mother by the flow of two nourishing liquids—milk and blood—both of which felt at that point sacred. The experience culminated in an experience of a numinous union with the Great Mother Goddess, rather than a human mother. Needless to say, I found the session profoundly healing…’

As a result of his experience in London, Stan occasionally used fusion therapy in the psychedelic research program at the Maryland Research Center, particularly in work with terminal cancer patients. In the mid-1970s, when we developed Holotropic Breathwork, anaclitic support became an integral part of our workshops and training”.

The Grofs then go into a major component of Holotropic Breathwork: being able to relive your own birth.

“Our life begins with a major traumatic experience—the potentially life- threatening passage through the birth canal, typically lasting many hours or even days. The memory of birth is a prime example of an “unexperienced experience“ that we all harbor in our unconscious psyche. Experiential work involving age regression has shown that it is associated with intense vital anxiety, feelings of inadequacy and hopelessness mixed with rage, and extreme physical discomfort—choking, pressures and pains in various part of the body.

The memories of prenatal disturbances and of the discomfort experienced during birth constitute a major repository of difficult emotions and sensations of all kinds and constitute a potential source of a wide variety of emotional and psychosomatic symptoms and syndromes. It is therefore not surprising that reliving and integration of the memory of birth can significantly alleviate many different disorders—from claustrophobia, suicidal depression, and destructive and self-destructive tendencies to psychogenic asthma, psychosomatic pains, and migraine headaches. It can also improve the rapport with one’s mother and have positive influence on other interpersonal relationships.

Certain physical changes that typically accompany the reliving of birth deserve special notice because they have a profound beneficial effect on the breathers’ psychological and physical condition. The first of these is release of any respiratory blockage caused by birth, which leads to significant improvement of breathing. This elevates the mood, “cleanses the doors of perception,“ brings a sense of emotional and physical well-being, increases zest, and engenders a sense of joi de vivre. The change in the quality of life following opening of respiratory pathways is often remarkable.

Another major physical change associated with the reliving of birth is the release of muscular tension, dissolution of what Wilhelm Reich called the character armor. This tension was generated as a reaction to the hours of painful and stressful passage through the birth canal under circumstances that did not allow any emotional or physical expression. After powerful and well-resolved perinatal experiences, breathers often report that they ate more relaxed than they have ever been in their life. This can be also accompanied by clearing of various psychosomatic pains. With the relaxation and relief from pain comes a feeling of greater physical comfort, increased energy and vitality, a sense of rejuvenation, and an enhanced ability to enjoy the present moment.

The Grofs then describe how past life memories are also particularly important. Although they always emphasise that they are not directing experiences, I would have to assume their discussion of the therapeutic potential and validity of these experiences would have some impact on workshop participants, leading up to their experience. For people living with a “treatment-resistant” mental health condition, this sounds like an answer:

“Particularly strong therapeutic changes are associated with what breathers experience as past life memories. These are highly emotionally charged experiential sequences that seem to take place in other historical periods and other countries. They are typically associated with a strong sense of déjà vu and déjà vecu—a strong sense that what they are experiencing is not happening to them for the first time, that they have seen or experienced it before. Past life experiences often seem to provide explanations for otherwise obscure aspects of the breather’s current life—emotional and psychosomatic symptoms, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, passionate interests, preferences, prejudices, and idiosyncrasies.

The full conscious experience of these episodes, the expression of the emotions and physical energies associated with them, and reaching a sense of forgiveness can have remarkable therapeutic effect. It can bring the resolution of a wide array of symptoms and disorders that previously resisted all attempts at treatment. People who have these experiences typically discover that situations that happened in other historical periods and in various parts of the world seem to have left deep imprints in some unknown medium and have played an instrumental role in

the genesis of their difficulties in the present lifetime.

The archetypal realm of the collective unconscious is an additional source of important therapeutic opportunities. Thus experiences of various archetypal motifs and encounters with mythological figures from the pantheons of different cultures of the world can often have an unexpected beneficial influence on the emotional and psychosomatic condition of the breathers. However, for a positive outcome it is important to avoid the danger of ego inflation associated with the numinosity of such experiences and to reach a good integration. Of particular interest are situations where the archetypal energy underlying various disorders has the form of a dark, demonic entity. Emergence into consciousness and the full experience of this personified energy often resembles an exorcism and can have profound therapeutic impact (see pages 194ff.)”

Repressed memories and sexual trauma

CW: This section includes graphic/violent details of sexual abuse and discussion of the abuse in MAPS Phase II clinical trial of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.

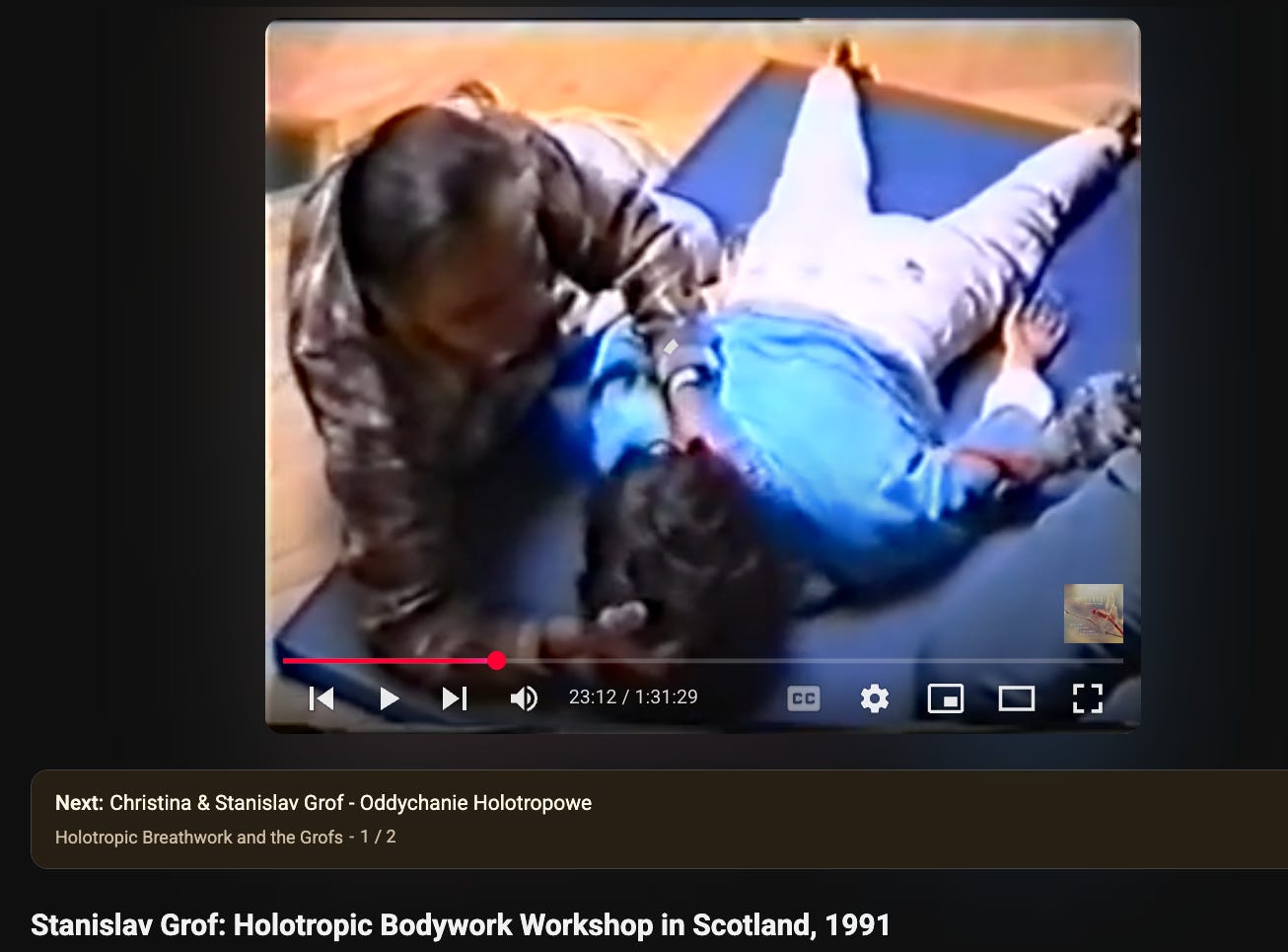

At the end of the documentary 1994, they show participants sharing their experiences from their breathing sessions. One man shares how he uncovered repressed memories of sexual abuse. His mandala shows him feeling like he was going to self-immolate, and that this was a reality. He discovers this was his rage for the abuse. They cut to a clip of him screaming, lying belly down with a ‘sitting’ laying over him, holding him down.

Another participant talks about recovering repressed memories of being gang raped by soldiers in a past life. This isn’t the first time she has started to uncover these memories. In a previous session, she recovered memories of their boots and being in the mountains. In her session that day, Stan encouraged her to stay with the memory and the breath. This allowed her to remember the full assault, with the support of Stan and her sitter. The camera cuts to her screaming, and kicking with stan and another man holding her arms down on either side.

She describes how reliving this repressed past-life trauma allows her to see her childhood feelings of not wanting to be a girl, and feeling worthless her whole life.

She adds, with prompting from her sitter, that she has also relieved her lower back pain and feels like she is “in a new body” after the experience. The documentary ends here, cutting to a voice-over letter viewers know they can send $3 to the address below if they would like a list of certified Holotropic Breathwork facilitators. Christina and Stan’s description of Holotropic Breathwork.

Other documentary footage from a workshop at the Findhorn Foundation in Scotland in 1991 shows them demonstrating bodywork techniques for sexual abuse victims. This was extremely disturbing to watch.

The footage from Scotland is dubbed in Russian, and I cannot make out everything they’re saying in English. If anyone knows where I can find a non-dubbed version, please let me know.

Here’s what I can gather:

“Stan: The other really powerful way, which I usually ask women to do that, because if it comes from a man, it can just bring a lot of material related to sexual violence, intrusion so on…

Christina says something always letting them now we’re cooperating.

Stan: we’re usually repeating, repeating that you can stop, so that they always know that they are in change. And the instruction is to tense of the knees and hold the knees together. This can bring an enormous amount of material, an enormous amount of emotion. There are a lot of sexual blockages around it.

There are all kinds of situations where there can be specific blockages or tensions in the very complex muscalar structures around the pelvis. Sometimes, it could be in this kind of tension, you are looking for different situation, until that person will tell you that is intensified by what you’re doing. Again, it’s not an area where you want to go in there poking muscles, so you do that by different mechanical tension.

Of note, Richard Yensen attempted a seemingly similar technique in the Phase II trial footage when he asked the victim-survivor if they wanted to try spreading their legs. It’s an inexplicably inappropriate and appalling suggestion. I strongly reject the entire premise of this approach, which is the idea that there are energy blocks in the pelvis that need to be cleared.

Grof also writes about the responsibility of the sexual assault victim for their abuse. In his first book, Realms of the Human Unconscious, Grof discusses the treatment of a sexual assault victim, Renata.

“Renata, a thirty-two-year-old housewife, was repeatedly hospitalized in mental institutions for severe cancerophobia, obsessive-compulsive ideation and behavior, deep suicidal depressions, a tendency toward self-mutilation, and borderline psychotic symptoms…Renata also had considerable problems in her sexual life. It was extremely difficult for her to form intimate relationships and her experiences with men were rather traumatic and confusing. Instances of brutal sexual approaches and attempted rapes were the prevailing pattern. She had never experienced an orgasm during sexual intercourse. Sexual excitement regularly precipitated feelings of panic, intense fear of death, and, later, accentuation of her cancerophobia….After a few years o f marriage, she refused intercourse altogether; this coincided with the mentioned finding of the cervical ulceration. The husband, unable to find an outlet for his frustrated sexuality, grew increasingly impatient with this abnormal situation.

He started molesting Renata, and, confronted with her decisive resistance, started abusing her physically and finally made several attempts at violent rape. Simultaneously, quite similar things were happening to Renata at her job. Several of her coworkers, independently of each other, became involved in a peculiar flirtation game with her. The resultant series of open sexual attacks frightened, puzzled, and irritated her. Memories of the above sexual assaults by her husband and coworkers formed the most accessible layers of this COEX system…

Once the traumatic experience was relived and integrated, Renata realized how deeply her neurotic symptoms and irrational behavior were related to the core experience.…Renata also recognized to what extent she herself played a key role in the later repetitions of her traumatic encounters with men. It was an unusual combination of flirtation and seductive behavior with resistance and rejection that had a powerful sexually stimulating effect on her husband and her coworkers, and finally drove them to molest and assault her”.

The description of Renata’s case involves a number of other gratuitously violent descriptions of sexual abuse that I won’t repeat here. This is a theme in all of Stan’s writing—the details are obscene, vivid and fully recounted.

Grof continues to theorise about Renanta’s responsibility for being raped by men:

Renata was obviously a predominantly passive victim in the nuclear traumatic situation; although she might have contributed to it by her childish coquetry and seductiveness, it was her stepfather who played a major role in setting the pattern. In her later life, however, she unconsciously structured her relationships with men according to the old pattern and played a very active and important role in its many subsequent traumatic repetitions. The unusual accumulation of sexual assaults and attempts at rape is certainly far beyond any statistical probability and strongly indicates that her contribution to these scenes of sexual traumatization was essential…

This is the revolutionary book that Michael Mithoefer and Rick Doblin were transformed by, leading to MAPS and the Mithoefer et al. manual for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.

I’ll end on the Grofs’ statement on “Holotropic breathwork and the academic community”

To our knowledge, only in Austria, Brazil, and Russia has Holotropic Breathwork been accepted as an official treatment modality1. The reasons are easily understandable; both the practice and theory of this new form of self-exploration and therapy represent a significant departure from current therapeutic practices and conceptual frameworks. Work with Holotropic Breathwork and with holotropic states of consciousness, in general, requires radical changes of some basic premises and metaphysical assumptions, which professionals committed to traditional ways of viewing the world and the human psyche are not ready to make…

We are currently experiencing a dangerous global crisis that threatens the survival of our species and life on this planet. In the last analysis, the common denominator of many different aspects of this crisis is the level of consciousness evolution of humanity. If it could be raised to a higher standard, if we could tame the propensity to violence2 and insatiable greed, many of the current problems in the world could be alleviated or solved. It seems that the changes regularly observed in people who have undergone the transformation described earlier would greatly increase our chances for survival if they could happen on a sufficiently large scale. We hope that the information in this book concerning the potential of holotropic states of consciousness, in general, and Holotropic Breathwork, in particular, will provide useful guidance for those who decide to take this journey as well as those who have already chosen it”

This was published in 2010. Little did Grof know that just 15 years later, Australian psychiatrists and psychologists would be training and implementing MDMA-assisted psychotherapy based on Holotropic Breathwork principles.

Getting sexual assault victims to heal their trauma so they can stop inducing men to sexually abuse them?